Why do they go through the leg for heart procedures?

A few years ago, in the clinic, I was explaining the details of a Catheter Ablation procedure to a patient. He was troubled by his Atrial Fibrillation and keen to have something done. I explained that the thin catheters are passed up from the groin to the heart and the ablation treatment is applied to the area where AF comes from. I completed my explanation of the risks and benefits as usual. During my explanation, I saw his face drop, his mood changed and I was worried I had said something to offend him.

From then on, he just wanted to discuss alternatives to Catheter Ablation and so we did. At the end of our consultation, I asked what put him off the idea of Ablation – was it the risks, the waiting times, the idea of wires in his heart? He said "I just don’t think it would fit for me – I think if you tried to pass those tubes up my little fella, it just would not work. He had got the wrong end of the ‘stick’ and his interpretation of groin was more mid-line than I had intended. 🫢

From that day, I have changed the way I explain the procedure- swapping out “groin” for “top of the leg” and double-checking that patients truly understand what I am trying to explain. This sets us up nicely for the rest of this post explaining why the top of the leg is used as the access point for many cardiac procedures.

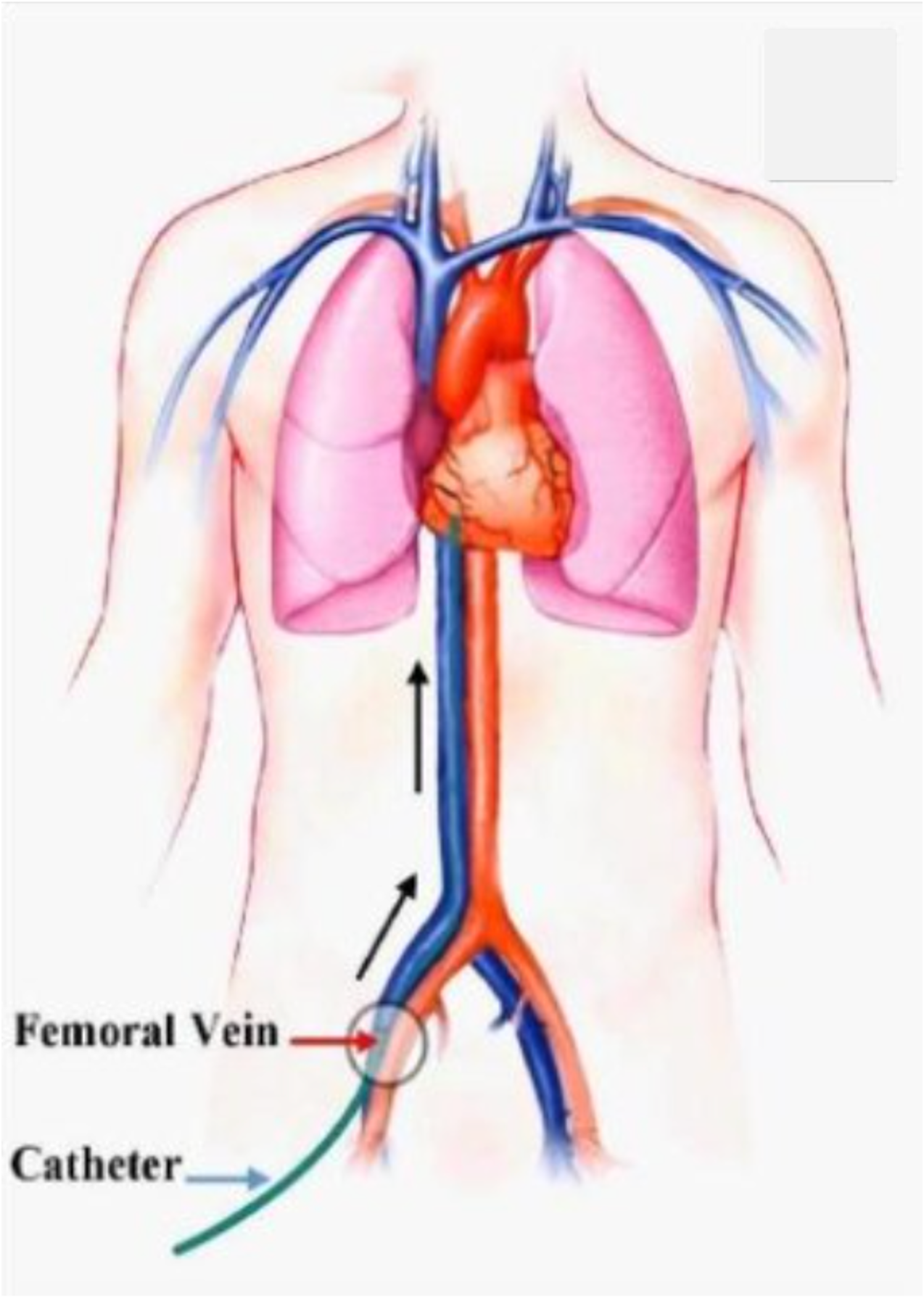

The journey from leg to heart

The heart is the centre of the cardiovascular system. This means all veins and arteries eventually lead to the heart.

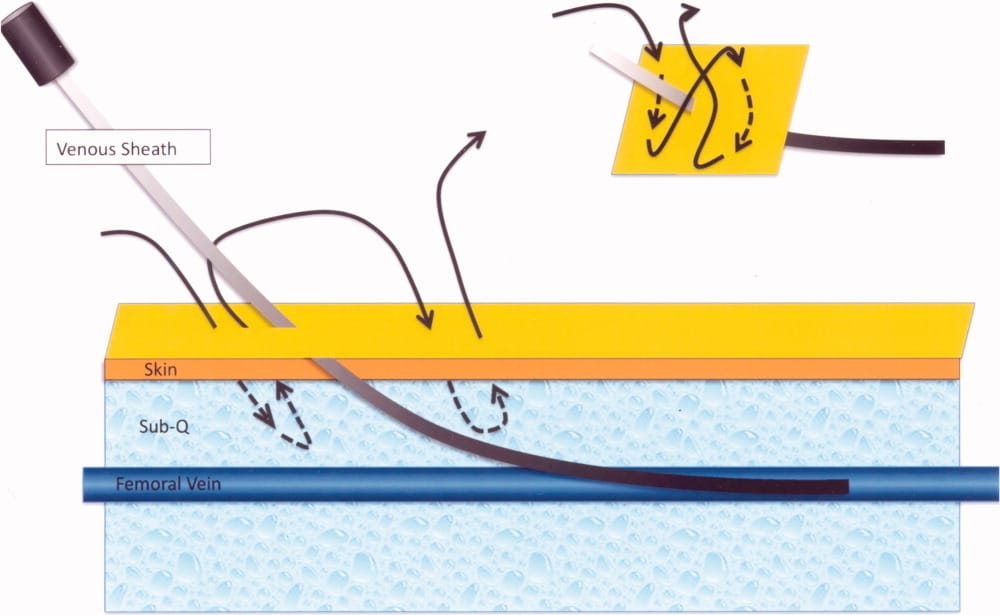

If you place your 4 fingers at the crease of your right leg and abdomen for 10 seconds, you will feel your “femoral pulse”. At this position, sit the femoral vein and femoral artery- two large blood vessels that sit less than a few centimetres beneath the skin (for most people). They are a direct highway up to the heart (again in most cases). The femoral vein, rather than the femoral artery is the chosen access point for heart procedures because it is large and expandable enough to fit multiple catheters in and also superficial enough to access with a needle and press directly on to close up at the end of the case. The vein is used for heart rhythm procedures as it connects directly to the right atrium of the heart without any valves that block the path giving access to atrial ablation procedures. The vein is also lower pressure than the artery so there is less risk of bleeding too. However, the vein and artery lie next to each other so can be hard to discern.

The risk of access site complications is very low- and getting lower.

Doctors used to rely on palpating the artery with their hands to find the femoral artery pulse. They would then aim to avoid it but be close enough to it in the hope of finding the femoral vein. Only after piercing it would you get an idea of whether it was an arterial spurt or a venous dribble that you had just punctured.

Even then, if you had punctured the artery, as long as you recognised you had done it, if you stopped and pressed on it for 10 minutes it would very often stop bleeding and you could try again. Cardiologists did so many of these cases that they got incredibly good at femoral vein access and the risks of this approach were very low..

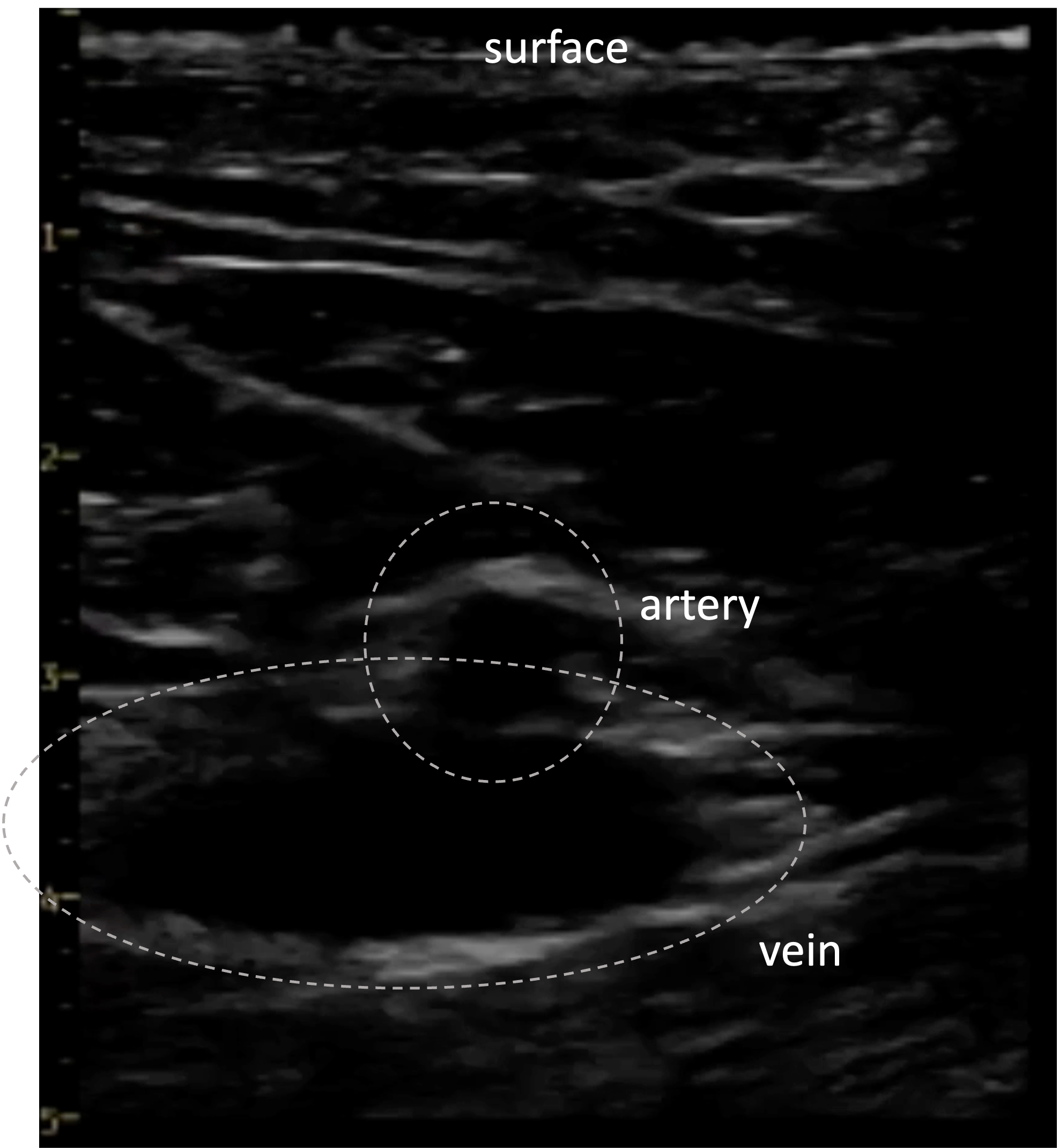

However, in a drive to bring this rate down further, many Cardiologists use Ultrasound to visualise the blood vessels during the puncture. This zero-radiation modality allows you to identify the vein and continuously watch as you track your needle down towards it. If you look at the picture below, the blood vessels both appear round and black on the image.

Often, the vein appears larger than the artery. A better telltale sign can be that when you press down- the vein should be easily collapsible whereas the artery, with stiffer walls, is less compressible- see the video below.

Direct visualisation with ultrasound evidence has reduced the rate of complications further. In an audit of our Arrhythmia procedural cases at Barts, where most cases are guided by ultrasound, 23 out of 5514 had femoral access complications which were less than 0.5% or less than 1 in 200. This has been especially helpful for obese patients or patients with vascular disease.

What happens at the end of the procedure?

Once all treatment has been delivered and the case is finished, the catheters have to come out. Although small, there is still a small hole in this blood vessel and, just like a blood test from the vein in your arm, if pressure is not applied it will bleed. In the same way, the simplest strategy to prevent bleeding is to just press on the puncture point for 10 minutes and give the hole time to heal up. Although this is sufficient for some procedures, cases like AF ablation use larger catheters and would require 60+ minutes of pressing to heal- not ideal for the patient nor the staff. So different tools have been developed to apply pressure to the puncture site and the one selected will depend on your procedure and operator preference.

These can include:

- A Femostop - an inflatable half-ball that presses down on the puncture point instead of using hands. The pressure can be adjusted by pumping it up like a blood pressure cuff:

- A Z-suture - a loop stitch that is pulled tight to apply pressure to the vein by squeezing the tissue around it tight. This can be left in for 2 hours and then snipped once the vein has healed.

- A ‘vascular closure device’- these devices are threaded into the vein and can apply a plug of glue directly onto the vessel wall which immediately stops the bleeding and degrades over time once things have healed. Although they sound efficient, they can be quite fiddly to apply and are expensive.

Summary

So the femoral vein is a sensible access point for intra-cardiac procedures like AF ablation and the risk of this approach is very low, especially if Ultrasound is used by the operator. Be sure to let your team know if you have any vascular disease or have had any surgeries or injuries to the groin…top of your leg.