The Next-Generation of Blood Thinners: The Newer Oral Anticoagulants on the horizon

Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban or Dabigatran - can we do better?

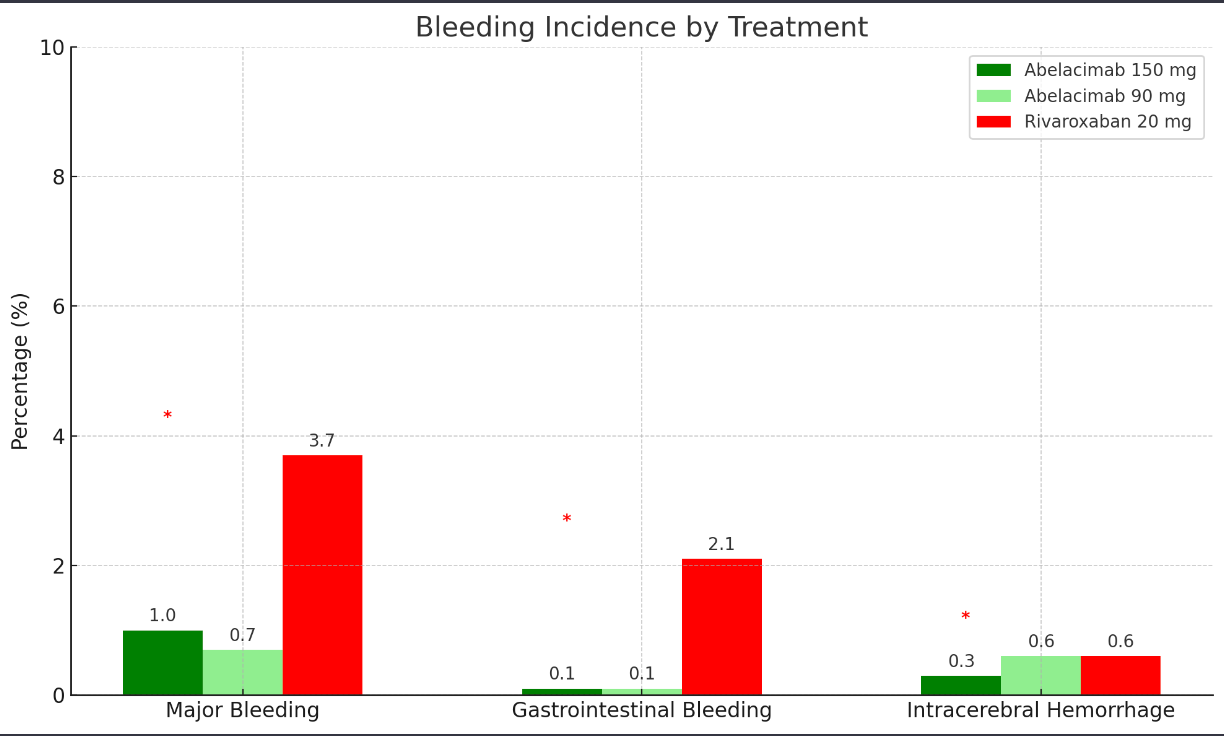

The problem with the latest generation of blood thinners- the “direct oral anticoagulants” named above is that they’re so good at doing what we want them to (prevent strokes) we can forget that 1 in 10 patients can still experience bleeding side effects whilst on them. 1 in 10 was the incidence of bleeding in the DOAC mega-trials, the rate of major bleeding was lower, around 2-3% per year.

Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban or Dabigatran. (Or Xarelto, Eliquis, Lixiana and Pradaxa) are the Gold standard of blood thinners in 2024 for patients with AF.

Yet, despite this risk prescribing blood thinners is the single most beneficial intervention we can do for patients with AF. DOACs save lives and prevent strokes. Beyond AF, they can help patients with Blood Clots and Heart Attacks too.

Is bleeding unavoidable?

Bleeding is viewed as an unavoidable side effect of anticoagulant therapy. But what if there was a blood thinner that could prevent strokes without the risk of bleeding?

This would be having our cake and eating it too! That appears to be what we’re seeing with the Factor 11 (or Factor XI using Roman numerals as is the convention) Newer Oral Anticoagulants.

Is it scientifically possible?

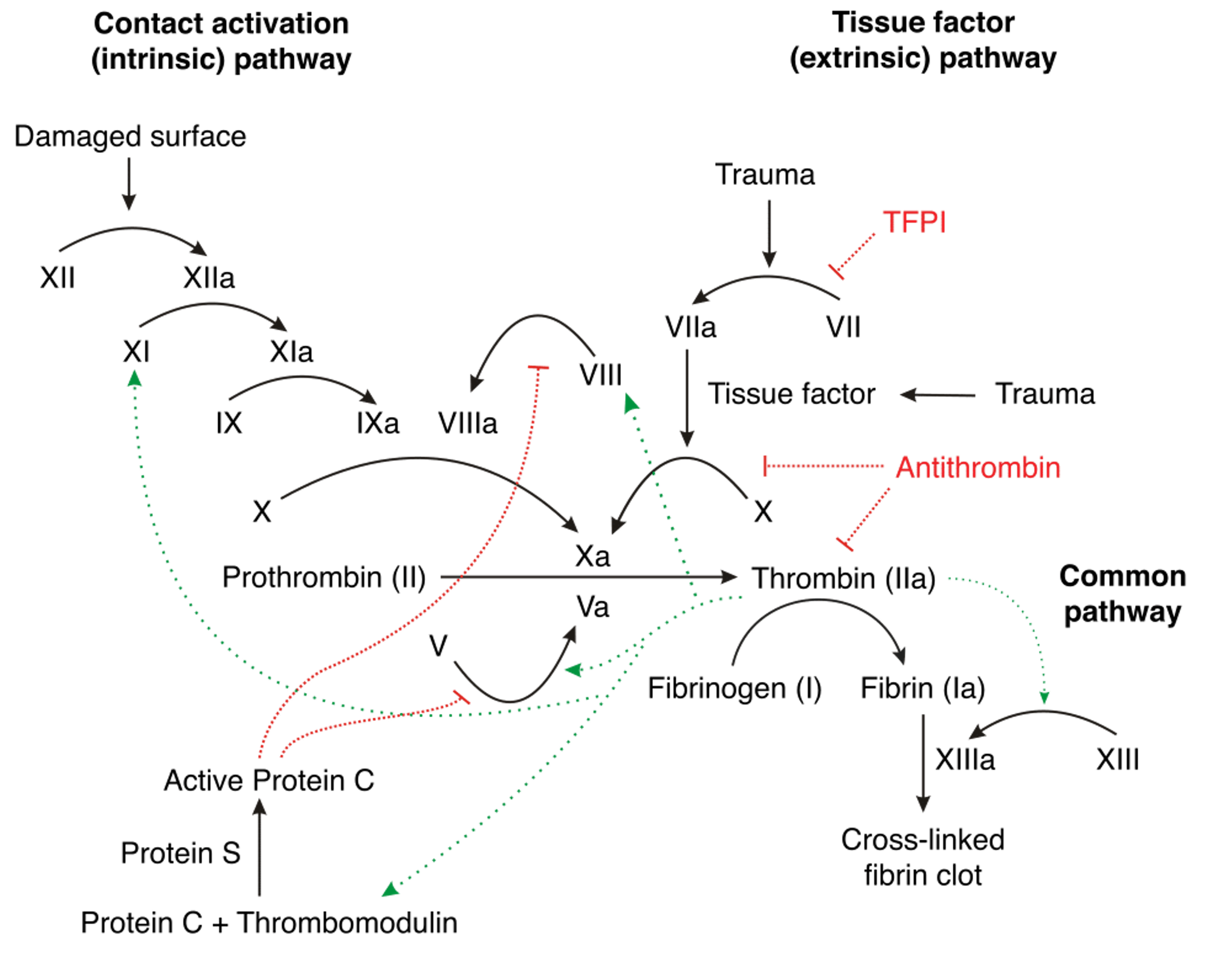

We are taught the ‘clotting cascade’ in medical school. I still remember drawing out the flow chart repeatedly to commit it to memory. It involves different “Factors” working together to respond to bleeding to stop it by forming a clot.

All the science in 60 seconds ⏱️

In 60 seconds, I will explain the science behind the Factor 10a inhibitors we use today (Rivaroxaban, Edoxaban and Apixaban) and the new Factor XI inhibitors:

A tear in the blood vessel causes Factors to be released that convert Prothrombin to Thrombin which converts Fibrinogen to Fibrin which binds together to form a blood clot. The clot blocks the tear, allowing time for the vessel to heal itself without the continuous leaking of blood.

The Direct Oral Anticoagulants (Rivaroxaban, Apixaban and Edoxaban) act directly on this pathway by blocking Factor Xa which is responsible for the conversion of Prothrombin to Thrombin (Dabigatran works a little differently by blocking Thrombin). So they prevent clot formation- reducing the risk of stroke but also delaying the physiological process of clot formation, hence the bleeding risk.

Factor XI is an amplifier. It is involved in a chain reaction that scales up the clotting response. However, it seems that this process is not as important in stopping bleeding and that haemostasis (the healing up of a torn blood vessel) can continue relatively unencumbered if this amplification process is blocked. So blocking Factor XI appears to stop pathological clot formation whilst allowing the physiological healing of bleeding.

It seems obvious when looking back at the science like this, but the two processes were always thought to be inseparably linked. The potential decoupling of the two pathways at Factor XI was realised from studies of patients with a genetic deficiency in Factor XI. Individuals with Haemophilia C lack Factor XI which is very rare. Clotting complications like strokes were unnaturally rare in these patients and their risk of bleeding complications was not high. This led investigators to study the role of Factor XI and make these advances in our understanding of the clotting pathway that was relatively static since the 1960s.

The Phase II trials show that it works

Phase one trials are tests in a small number of humans to confirm safety. Phase two trials are bigger and focus on evaluating the efficacy of a drug i.e. it does what it is supposed to do. And in 2023, we received Phase II data about Factor XI inhibitors.

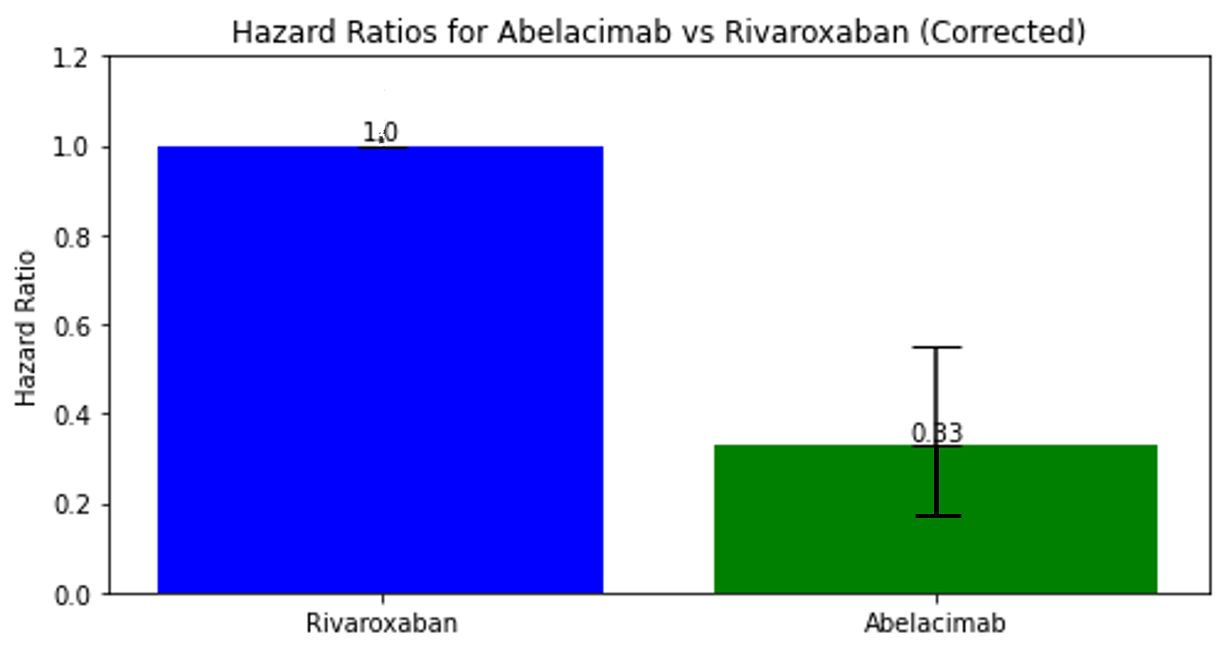

Several big pharmaceutical companies are developing Factor XI inhibitors, racing to get the trials complete and potentially bring the drugs to market. One such agent is Abelacimab. The Phase II trial results were shared at the American Heart Association meeting in November 2023. As this was a phase II trial, the Investigators wanted to measure if it led to less bleeding than Rivaroxaban. The trial was halted early because the rate of bleeding was significantly lower than Rivaroxaban. In 1200 randomised patients, the rate of bleeding was one-third that of patients on Rivaroxaban.

This is a positive sign for the one-a-month injectable drug but remember- a lower rate of bleeding is meaningless if it doesn’t also prevent strokes. That wasn’t assessed in this phase II study and we will likely see the Phase III study of Abelacimab launched in 2024- to see if it reduces the rate of stroke events whilst also giving this lower bleeding profile.

We have some Phase III data- reasons to be cautious.

Phase III data is designed to be comparative. To help establish the drugs relative role compared to other treatment options. In the case of Factor XI inhibitors, comparison against DOACs for stroke prevention is the critical question.

Asundexian is a Factor XI inhibitor tablet that showed lower rates of bleeding compared to Apixaban in the Phase II PACIFIC-AF trial. The results of this 862-patient trial also reported the results of bloodwork analysis that showed Factor XI activity was successfully inhibited and was published in the Lancet in 2022.

This laid the groundwork for the OCEANIC-AF; a phase III trial measuring the relative rates of stroke events in patients with AF taking Asundexian versus Apixaban. But in November 2023, Bayer, the pharmaceutical company that produce the drug and the Trial sponsors released a statement to say they were halting the trial after just 11 months due to lack of efficacy on recommendation of the Independent Data Monitoring Committee. As said before, lower bleeding rates are meaningless if we cannot demonstrate stroke rate reduction to atleast the level of the DOACs. We can’t comment further on the OCEANIC-AF trial and reasons for early termination and hope to read further results about the work in the future.

Will we see this new generation of blood thinners in 2024?

We are unlikely to see anything licensed in the next few years. The Trials of DOAC vs Warfarin enrolled 10-20,000 patients each and we will probably need larger numbers to complete a Phase III trial of a Factor XI inhibitor against them.

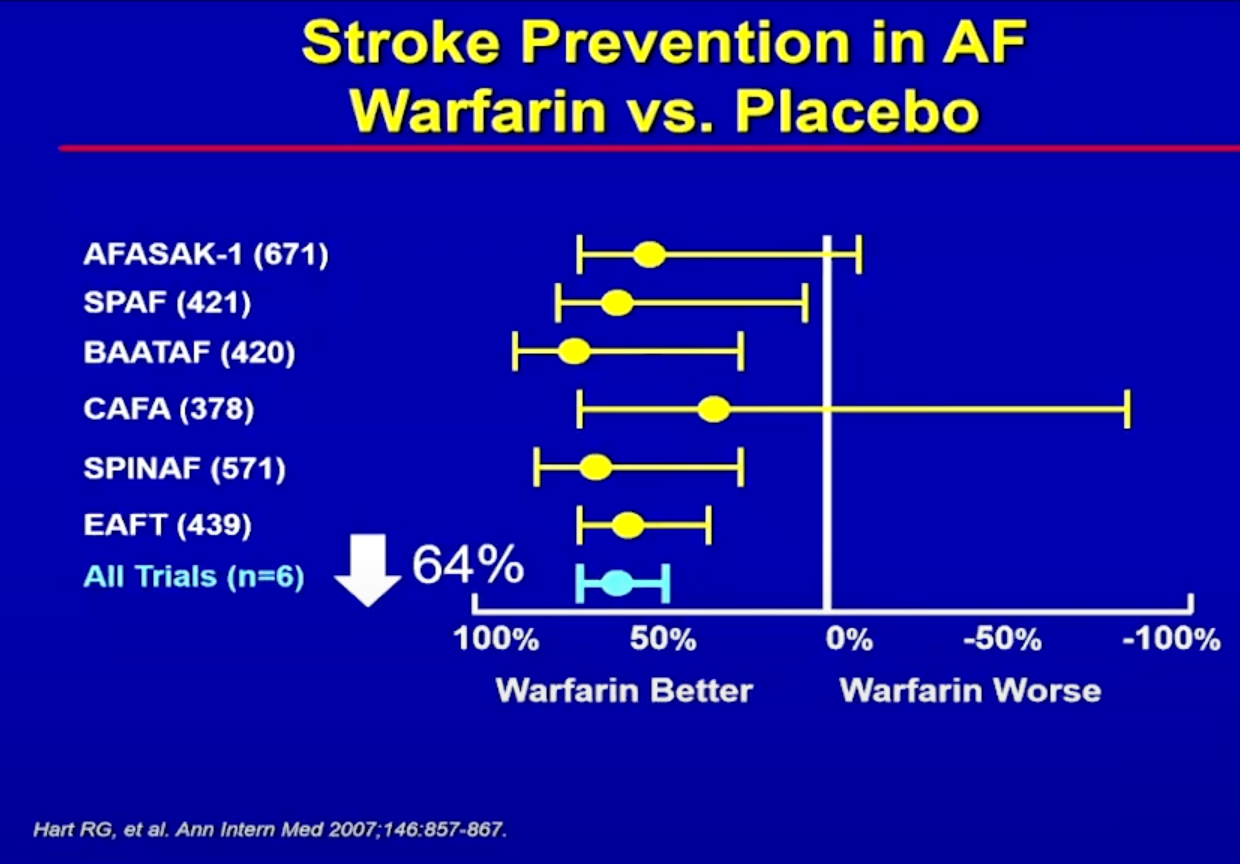

The bar for a better blood thinner is very high. Warfarin is an excellent blood thinner. It was the Gold Standard till 2010- with 12 trials, one after the other, showing the benefit of warfarin over placebo, over aspirin, over any other type of blood thinner.

Then in the 2010’s the DOAC megatrials were published, given us an even better option for most patients with AF. Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban and Dabigatran provide effective risk reduction for stroke events whilst providing a low bleeding risk- 2-3%/year risk of major bleeding in the big 4 trials of the 4 DOACs. So conducting a trial to show a significantly lower rate of major bleeding than this will require large numbers of patients and many years of data. Fortunately (or unfortunately) there is no shortage of patients with AF. And although 2-3% sounds small, it represents a large number of the millions of patients worldwide living with AF.

Many patients living with AF today are prohibited from taking blood thinners- their risk of bleeding is too high. A safer option may provide an option for this group of patients to safely lower their stroke risk without escalating their bleeding risk.

And a final thought- the cost of DOACs has reduced significantly over the last decade, especially in the UK and will likely do so in the USA as they come off patent. If the new Factor XI inhibitors do demonstrate a lower bleeding risk- perhaps 1%/year, what would be the cost that payers or patients would be willing to pay for this incremental benefit and can it be justified.