To cardiovert or not cardiovert?

Discover the best way to manage new-onset AF in the A&E. Is cardioversion necessary, or is a 'wait and see' approach just as effective? Read on to learn more.

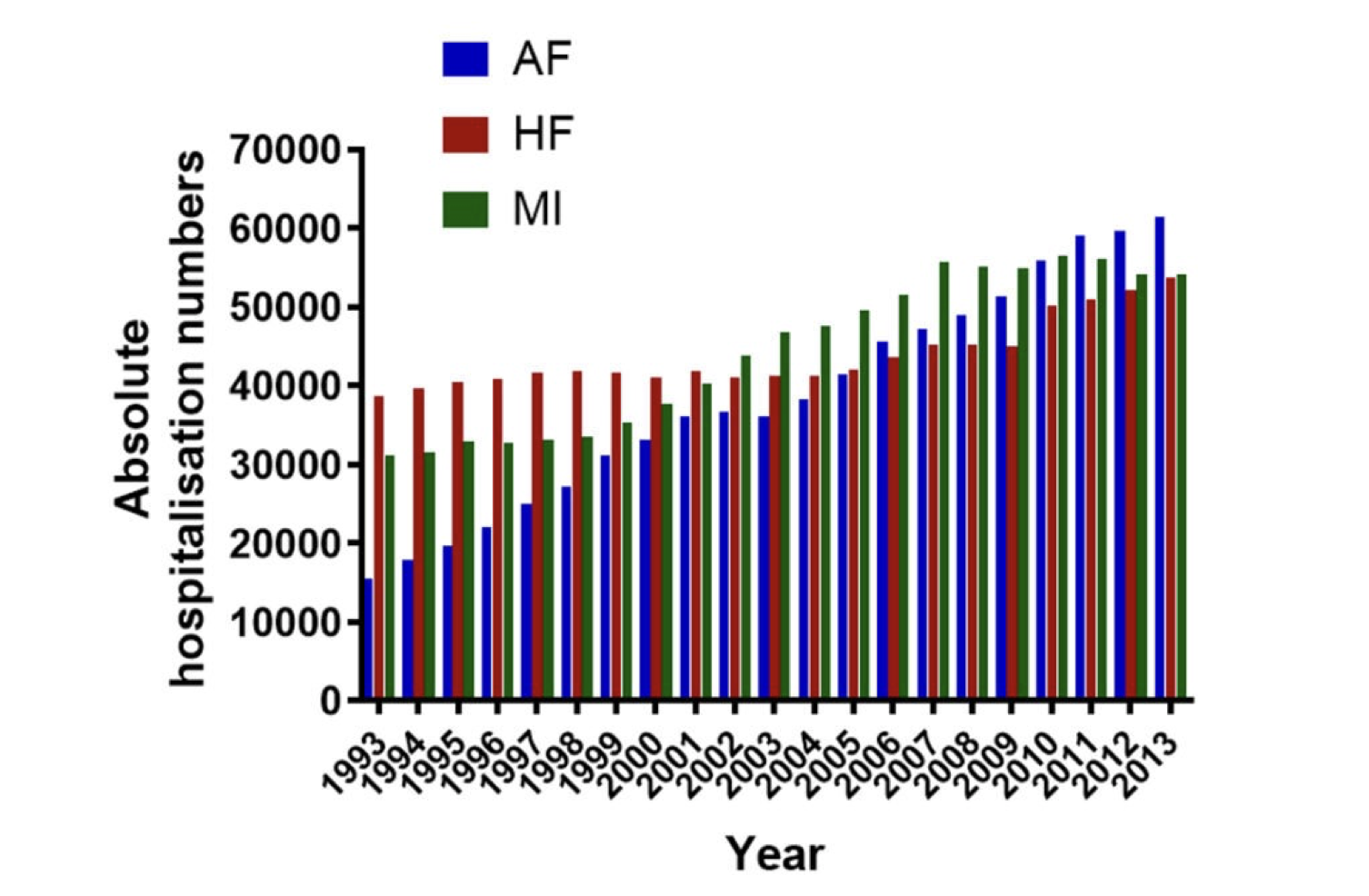

AF is a leading cause of emergency admission. Poorly controlled AF can be debilitating- leading patients to seek emergency attention through A&E. See the bar chart below for just how striking this increasing phenomenon is- it had become the leading cardiac cause of hospitalisation in Australia (prior to Covid).

With A&Es breaching capacity and patients queued up in corridors with long waits across the country (and world), understanding the best way to manage new-onset AF in the A&E is an important consideration from the hospital's perspective as well as the patient's perspective.

The quickest way to stop AF is with cardioversion (this can be done electrically with an electric shock under sedation or with specific medications). However, rate-controlled AF does not cause immediate damage to the heart and so if the symptoms can be controlled, is there any rush to do this? i.e. if the symptoms are tolerable can the patient be discharged home and come back to see a specialist another day? Does cardioversion in the A&E increase the chance of you being in normal rhythm further down the line?

I attended EUROPE-AF this week; a conference held in London for cardiologists with a special interest in AF where experts present important research on all things AF.

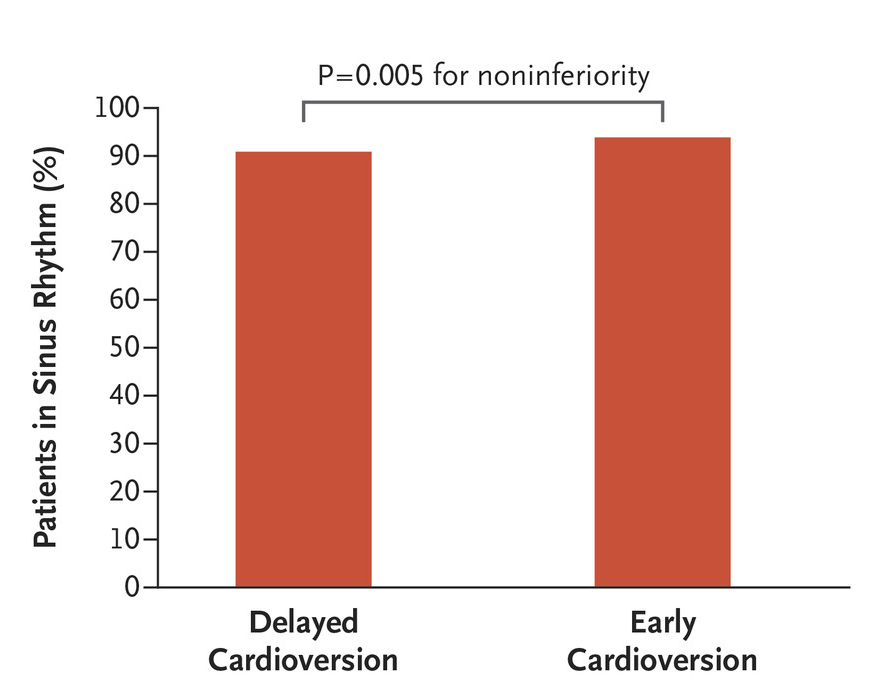

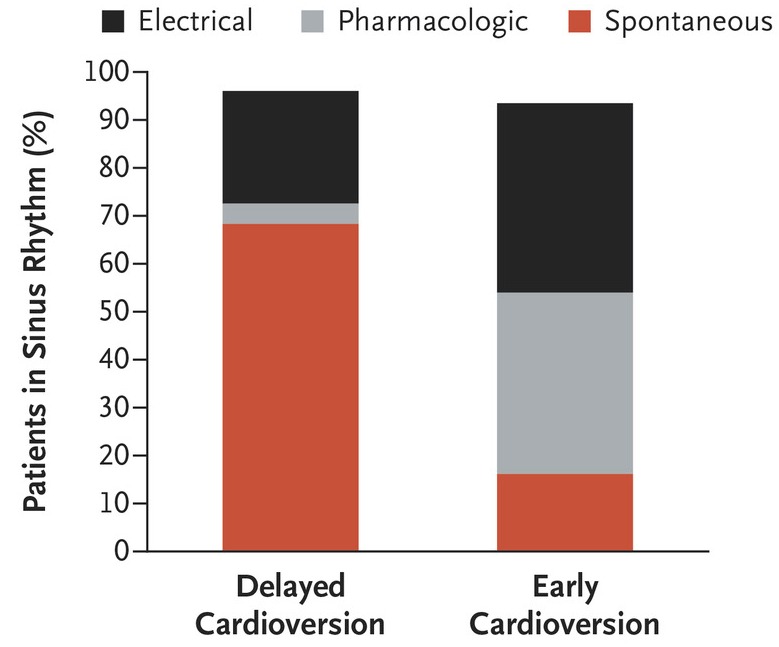

Harry Crijns is a leading AF researcher from the Netherlands and he presented the findings of the RACE-7 trial. This compared (option 1) cardioversion in the A&E versus (option 2) a 'wait and see approach'. In the 'wait and see' group, patients were given medicines to control their heart rate in the A&E, discharged home, and then brought back to a dedicated clinic 2 days later where they could be cardioverted if needed.

They enrolled 437 patients with new-onset (less than 36 hours) AF who presented to A&E. The headline result was whether you cardiovert them right there and then in A&E versus 2 days later, there was no difference in their heart rhythm outcomes 4 weeks down the line.

But Prof Crijns went on to present some of the more interesting findings-

- 70% of the 'wait and see' group of patients had spontaneously gone back to normal rhythm!

2. The average (median) time that patients in the 'wait and see' group spent in the hospital was LESS than those in the early cardioversion group.

3. Psychological impact: one criticism Prof Crijns received was that the 'wait and see' strategy would make patients anxious; that going home still in AF would cause patients anxiety. However, he felt this was not the case at all. In fact there may be a psychological advantage of discharging the patient home in AF- they can see first hand that staying in AF is not dangerous.

4. Doing an early cardioversion in the A&E did not appear to reduce any risk of heart failure, AF progression or strokes.

5. The risk of AF coming back was similar in both groups. A third of patients had recurrences, although only 7% had to come back to A&E for these.

6. Getting the medications right in the A&E may prevent fast AF coming back in the future. Whereas if a patient is cardioverted in the A&E, the doctors may overlook starting the right medicines.

So going back to that original question- how should we manage AF in the A&E? An important caveat is that this doesn't apply to patients with any features of instability i.e. blacking out, chest pains, very low blood pressure and it doesn't apply to patients who have persistent (continuous) AF.

But for patients with new-onset AF, even if it isn't the first episode, both options are reasonable and should be guided by the A&E's local set-up, expertise, and importantly, the patient's preference. RACE7 was another piece of evidence to suggest there isn't urgency to immediately convert patients out of AF and if patients can tolerate the symptoms, seeking specialist input in a non-A&E environment works well.

Pluymaekers NAHA, Dudink EAMP, Luermans JGLM, Meeder JG, Lenderink T, Widdershoven J, Bucx JJJ, Rienstra M, Kamp O, Van Opstal JM, Alings M, Oomen A, Kirchhof CJ, Van Dijk VF, Ramanna H, Liem A, Dekker LR, Essers BAB, Tijssen JGP, Van Gelder IC, Crijns HJGM; RACE 7 ACWAS Investigators. Early or Delayed Cardioversion in Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 18;380(16):1499-1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900353. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30883054.