Slow Atrial Fibrillation

Much of what we have explored so far relates to fast Atrial Fibrillation. However, the heart rate during AFib can slow, especially as patients become older, and this can also lead to troubling symptoms.

A lot of confusion can occur when slow AF is detected, and it can lead to misunderstandings that result in mismanagement. The first step is to break down what is meant by the term ‘slow AF’, as it can represent one of three different issues:

1. AFib with a slow ventricular rate

This is most commonly what is meant when a doctor or patient says ‘slow AF’. The paradox here is that the atrial rate during AFib is always fast. The "slow" part refers to the rate at which the bottom chambers (ventricles) are contracting. I will explain this further:

If you put a catheter into the top chamber of the heart (the atria) during AFib, you will see that it is beating more than 250 times per minute. If you opened the chest and looked at this chamber, it would be beating so fast it would appear to be vibrating (also known as fibrillating) — hence the term atrial fibrillation.

However, the main pumps of the heart, the ventricles, do not automatically conduct at this rate. There is a filter that sits between the atria and ventricles called the AV node, which blocks most of these beats. This structure allows between 1 in 5 to 1 in 2 beats to pass through to the ventricles, resulting in a ventricular rate of 50 to 150 beats per minute. During slow AF, the atrial rate remains above 250 beats per minute. The number of beats conducted through the AV node into the ventricles is what slows — resulting in Atrial Fibrillation with a slow ventricular rate.

A metaphor for this would be a woodpecker trying to peck a tree 250 times per minute, but missing most of the time and only making contact once every few attempts when everything is perfectly aligned.

- Over-medication

A common cause of Atrial Fibrillation with a slow ventricular rate is over-medication with rate control drugs. Medications such as bisoprolol, metoprolol, diltiazem, or verapamil act on the AV node and reduce the number of beats that are conducted across. As the dose increases, the rate becomes slower. If this causes the ventricles to beat too slowly, it can lead to symptoms.

This is not permanent — the rate increases as the dose is reduced and symptoms often resolve. Monitoring heart rate using a pulse oximeter, blood pressure machine, wearable monitor (or even just your fingers!) on a daily basis during any medication changes can help tighten this feedback loop and get the dosing right.

There have been case reports of bisoprolol-like eye drop medications (such as timolol or ‘Cosopt’, used in glaucoma) inadvertently causing a slow heart rate and symptoms. This is rare, as the doses are small and the drug does not reach high concentrations in the blood. However, if other causes of symptomatic slow ventricular rate have been ruled out, it can be something to consider.

- Age and slow AF

Age-associated changes in the heart’s conduction system can also affect the AV node. Again, the rate of atrial beating does not meaningfully slow, but fibrosis can affect the AV node, leading to slower conduction to the ventricles.

As a general rule, the ventricular rate slows with age — even in people without Atrial Fibrillation. As a result, medication doses may need to be reviewed and potentially reduced as patients get older.

Other conditions, such as abnormal thyroid function, can also cause a reversible slowing of the ventricular rate and should always be checked in a patient with a new diagnosis of AF or if the ventricular rate changes unexpectedly.

When to treat slow AF

There is no defined cut-off at which the AF ventricular rate becomes “too slow.” Treatment is guided by symptoms, which may include:

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Shortness of breath on exertion

- Exercise intolerance

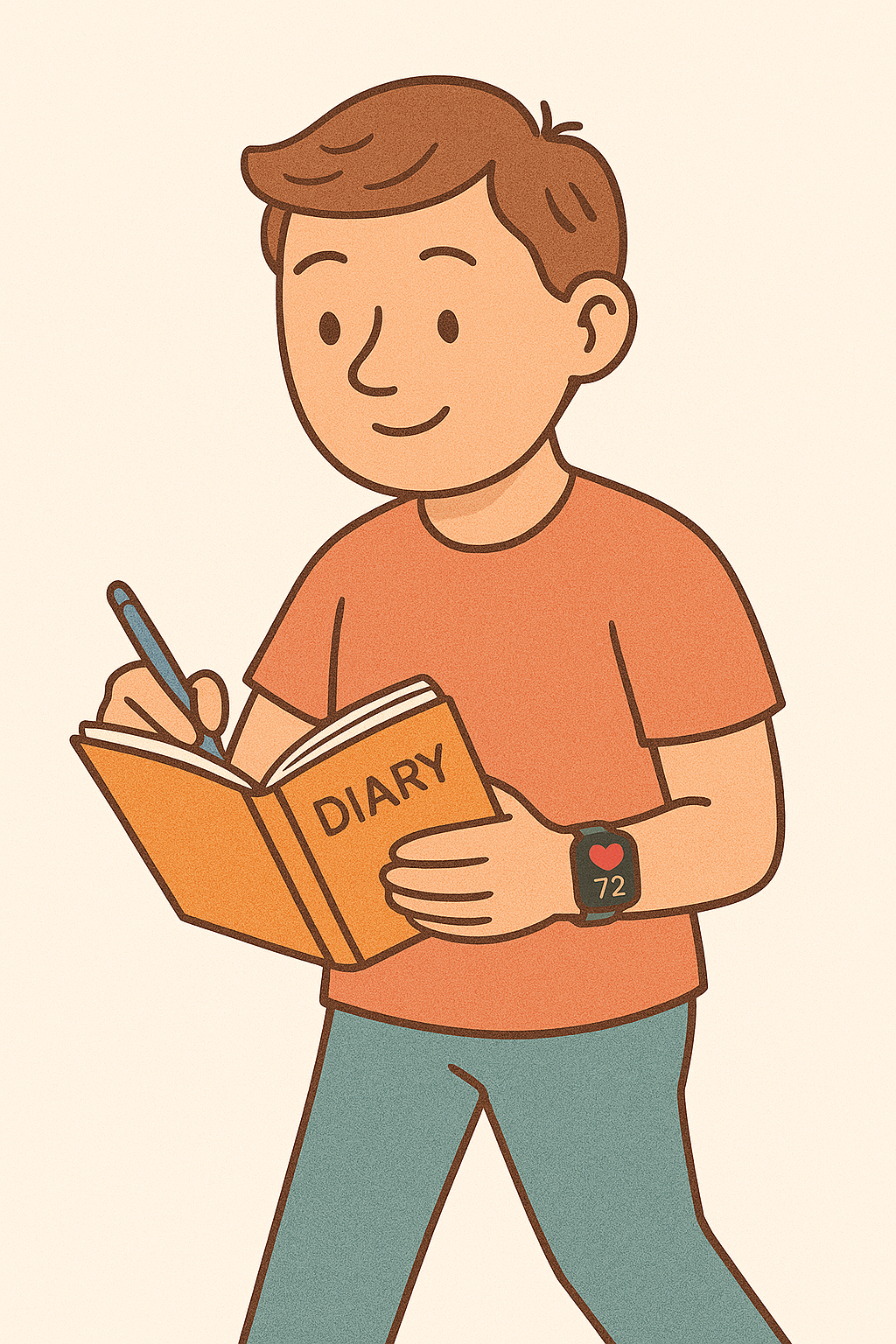

Tracking your heart rate using a wearable tracker can be useful to determine if symptoms correlate with a slow heart rate. This involves keeping a symptom diary over several days or weeks and comparing it to your heart rate recordings to see if symptoms consistently occur during slower heart rates.

If you want to try this, it’s important to remain ‘blind’ to the heart rate readings while logging symptoms. Seeing a heart rate of 50 bpm can, by itself, trigger anxiety or perceived symptoms and bias your reporting.

If a clear correlation is confirmed and all rate-slowing medications have been stopped, it may be appropriate to consider whether a pacemaker could help. This remains a grey area in the European guidelines for pacemaker implantation — in part because symptom-rate correlation is often poorly established.

In this scenario, a pacemaker acts as a safety net, preventing the heart rate from dropping to levels that cause symptoms. However, if the heart rate isn’t actually responsible for the symptoms, a pacemaker would not improve them.

Catheter ablation also plays a role in slow AF but the indication is more nuanced here. This is because the low ventricular rate is not caused by the fast atrial rate, but rather by the AV node conduction rate. So even if the AF is eliminated, the conduction disease may persist, resulting in a slow heart rate despite a return to sinus rhythm. That said, there are situations in which ablation can still be helpful, especially when trying to avoid pacemaker implantation — particularly if the symptoms stem from the irregularity of AF rather than the slow rate. Again, this is where the symptom diary becomes so valuable.

When I am on call for cardiology, a common referral is for incidentally detected slow AF (usually under 60 bpm) in a patient attending their GP or A&E for an unrelated reason and who has no related symptoms.

However, when these referrals are received, it’s important to explore what is actually meant by ‘slow AF’ — because there are two alternative conditions that fall under this umbrella but require very different treatment strategies.

2. Reversion pauses after AFib

Paroxysmal AF is an intermittent form of AFib, where the heart flits between normal sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation. After an AFib episode terminates, sinus rhythm resumes. However, Sinus Node Disease can coexist with AF and may result in a delay in the resumption of normal rhythm. This leads to a pause.

There is no risk of normal rhythm not returning — it always does — but if the interval pause lasts a couple of seconds, it can cause symptoms.

In this case, a person might describe their typical AFib symptoms followed by a dizzy or light-headed episode just before things return to normal. If these symptoms are troubling and consistent, treatment can include:

- Reducing the frequency of AF episodes (which prevents both the AF symptoms and the pause), or

- Inserting a pacemaker to provide a safety net and stimulate a heartbeat during the pause.

Choosing between these strategies (or none at all) is a very personal decision and should be made in consultation with a specialist AF doctor.

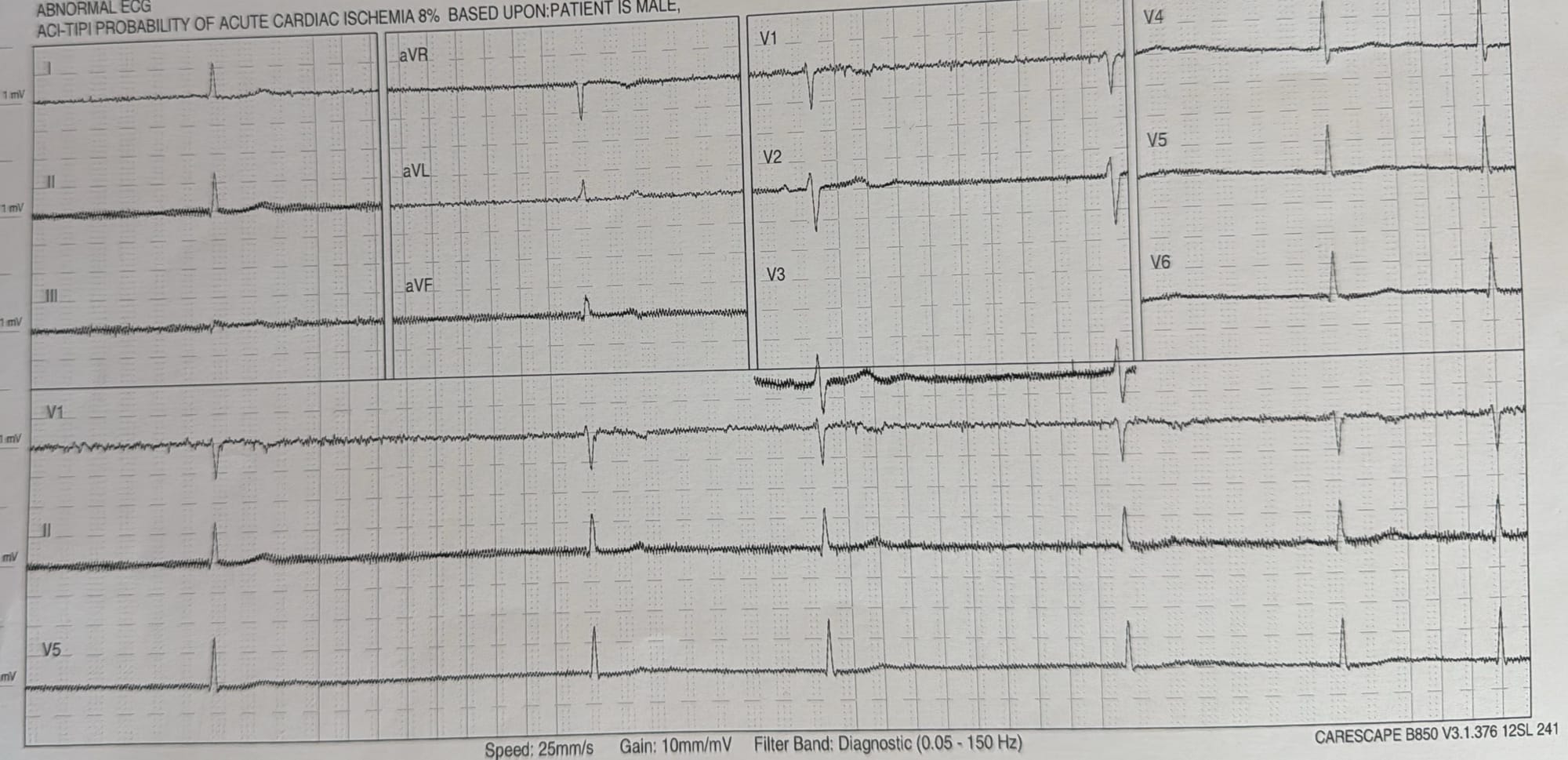

3. AFib with complete heart block

In rare cases, the AV node can become completely non-functional — meaning no atrial activity reaches the ventricles at all. In this scenario, the ventricles may initiate a backup rhythm at a very slow rate (often 35–40 bpm).

This is as if the woodpecker is still pecking furiously, but missing every single strike — not one gets through.

This type of rhythm looks very different on an ECG. In such cases, pacemaker implantation becomes an important — and often urgent — treatment.

This can’t be detected using heart rate monitoring alone. Although it is rare, timely diagnosis is critical, which is why an ECG is essential if the heart rate slows or becomes fixed at a low level, or if any new symptoms develop.

Additional reading:

The ESC pacing guidelines which include guidance on when pacemakers can be considered in slow AF: Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM, Barrabés JA, Boriani G, Braunschweig F, Brignole M, Burri H, Coats AJS, Deharo JC, Delgado V, Diller GP, Israel CW, Keren A, Knops RE, Kotecha D, Leclercq C, Merkely B, Starck C, Thylén I, Tolosana JM; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427-3520. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2022 May 1;43(17):1651. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac075. PMID: 34455430.

Much of what we have explored so far relates to fast Atrial Fibrillation. However, the heart rate during AFib can slow, especially as patients become older and this can also lead to troubling symptoms.

A lot of confusion can occur when slow AF is detected and it can lead to misunderstandings which results in mismanagement. The first step is to breakdown what is meant by the term ‘slow AF’ as it can represent one of three different issues:

- Slow AF means AF with a slow ventricular rate

This is most commonly what is meant when a doctor or patient says ‘slow AF’. The paradox here is that the atrial AF is always fast and the slow part of the heart is actually the rate at which the bottom chambers are contracting. I will explain this further:

If you put a catheter into the top chamber of the heart (the atria) during AFib, you will see that it is beating more that 250 times per minute. If you opened the chest and looked at this chamber it would be beating so fast it would appear to be vibrating (also known as fibrillating)- hence the term atrial fibrillation.

However, the main pumps of the heart, the ventricles do not automatically conduct at this rate, there is a filter that sits between the atria and ventricles that blocks most of these beats called the AV node. This structure allows between 1 in 5 to 1 in 2 beats to pass through to the ventricle, resulting in the ventricles beating 50 to 150 times per minute. During slow AF, the atrial rate remains >250 beats per minute. The number of beats conducted through the AV node and into the ventricles is what slows- resulting in Atrial Fibrillation with a slow ventricular rate.

A metaphor of this would be a woodpecker, trying to peck a tree 250 times a minute but it misses most of the time and only makes contact once every couple of attempts when everything is perfectly aligned.

Over-medication

A common cause for Atrial Fibrillation with a slow ventricular rate can be over-medication with rate control medication. Medicines like bisoprolol, metoprolol, diltiazem or verapamil effect the AV node and reduce the number of beats that are conducted across. As the doses are increased, the rate becomes slower and if this causes the ventricles to beat too slowly, it can lead to symptoms. However, this is not permanent and the rate increases as the dose is reduced back down and symptoms resolve. Monitoring heart rate using a pulse oximeter, blood pressure machine, wearable monitor (or even just your fingers!) on a daily basis during any medication changes can be helpful to tighten this feedback loop and get the dosing right.

There have been case reports of bisoprolol-like eye drop medications, timolol or ‘Cosopt’ used in glaucoma inadvertently causing a slow heart rate and symptoms but this is pretty rare as the doses are small and it does not reach high concentrations in the blood. However, if other causes of symptomatic slow ventricular rate have been ruled out, it can be something to consider.

Age and slow AF

Age-associated changes in the conduction system of the heart also occur which affect the AV node. Again, the rate of atrial heating does not meaningfully slow, but fibrosis can affect the AV node meaning it conducts down to the ventricles at a slower rate. As a general rule, the ventricular rate therefore slows as we get older (even for individuals without Atrial Fibrillation) and so medication doses may need to be reviewed and potentially reduced as patients get older.

Other conditions such as abnormal thyroid function can also cause a reversible slowing of ventricular rate and so should always be checked in a patient with a first diagnosis of AF or if the ventricular rate unexpectedly changes.

When to treat slow AF

There is no cut-off at which the AF ventricular rate becomes too slow. Treatment is guided by symptoms, which can manifest as:

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Shortness of breath on exertion

- Exercise intolerance

Tracking your heart rate using a wearable tracker can be useful to determine symptom-rate correlation. This involves keeping a symptom diary to record these symptoms over a period of days to weeks and then marrying that up with your heart rate recordings to see if the heart rate was consistently slower during times of symptoms. If you want to trial this, it is important to remain ‘blind’ to the heart rates during the period of symptom reporting. This is because seeing a heart rate alert of 50 beats per minute can artificially induce symptoms and bias your reporting.

If symptom-rate correlation is clearly confirmed and all rate slowing medications have been stopped then it can be appropriate to consider whether a pacemaker could help these symptoms. This is very much a grey area in the European recommendation guidelines for pacemakers- in part because symptom-rate correlation is done so poorly. In this circumstance, pacemakers act as a safety net, to prevent the heart rate dropping to the levels that cause symptoms. But if the heart rate is not the cause for symptoms then a pacemaker would not alleviate this.

Catheter ablation has less of a role in slow AF also as the low rate is not a result of the fast heart rate in the atria so much as it is due to AV node. So even if you eliminate the AF, the slow rate of conduction through the AV node disease persists and so even if the rhythm returns to normal, the rate would remain slow. However, again there are circumstances where catheter ablation does alleviate symptoms when the symptoms are due to the irregularity of AFib and less attributable to the slow rate itself. Another reason that the symptom diary is so useful.

When I am on call for Cardiology, a common referral is for incidentally detected slow AF (usually less than 60 beats per minute) in a patient attending their GP or A&E for an unrelated reason and has no related symptoms.

However, when these referrals are received, it is important to properly explore what is meant by ‘slow AF’ because there are two alternative conditions that are tagged under this umbrella that require different management strategies.

- Reversion pauses

Paroxysmal AF is the intermittent form, wherein the heart flits between normal sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation. After an AFib episode terminates, sinus rhythm resumes. However, Sinus Node Disease can co-exist with AFib and this may result in a delay in the resumption of normal rhythm after an AFib episode resulting in a pause. There is no risk of normal rhythm not coming back (it always does), but if these interval pauses last a couple of seconds they can cause symptoms.

In this circumstance, a person would describe their typical AFib symptoms and then a dizzy or lightheaded episode at the end before everything settled down and went back to normal. If these symptoms are troublesome and consistent. The treatment strategy here can involve trying to reduce the frequency of AFib paroxysms as that would address both the symptoms during AFib as well as the symptoms during the subsequent pause by preventing it happening. Alternatively, a pacemaker would act as a safety net to stimulate the heart beat during the pause. Deciding which treatment (if any) is best in this circumstance is a very personal decision and should be made in consultation with an AF specialist doctor.

- AFib with complete heart block

In rare cases, the function of the AV node that connects the atria to the ventricles can become severed, meaning that no atrial activity filters through (i.e. the woodpecker is missing every peck on the tree). The ventricles may be able to generate a back-up beat at a slow rate of 35-40 beats per minute when they are not receiving any stimulation from the AV node. This can look very different on an ECG, but in this circumstance, pacemaker implantation becomes an important and urgent treatment. This can’t be detected using heart rate monitoring alone. Although rare, diagnosing this is time critical hence why an ECG is important if the heart rate slows or becomes fixed at a low rate, or if any new symptoms develop.