Screening for AF

This is a really controversial topic! The reflex opinion (especially amongst patients with AF or healthcare professionals managing AF) is often SCREEN EVERYBODY- the more AF we can find the more patients we can treat.

But there are several important considerations before launching a screening programme:

Should we screen everyone? Kids, adults, elderly?

How often should we screen people? One check per year? Every year

How should we screen? A single ECG? A Holter monitor? Theres emerging evidence for patch monitors, wearable monitors and implantable devices too.

Is it value for money?

Even if we do screen people and prove we can detect AF, can we then do something that will improve their health outcomes?

This last point is the one we really need to address first. Because the other points can be seen as the details we can tweak to optimise the program but this last point of ‘actionability’ is critical to justify having a screening programme at all.

There are 2 main reasons for treating AF:

- To reduce the impact of AF symptoms

- To reduce the risk of stroke.

Screening is, by definition, about trying to identify disease in asymptomatic people. So improving health outcomes by treating symptoms in asymptomatic people doesn’t make any sense. So then the question really revolves around whether the detection of AF through screening can result in a reduction in their stroke risk, perhaps using blood thinners in these patients.

Sweden has a great setup for performing population-level clinical interventions and a group from Stockholm recently published the findings of the STROKESTOP study which gives useful insights into this issue.

Between 2012-2014, the researchers enrolled more than 28,000 people between the ages of 75 and 76 years old. They were randomly allocated 50%:50% to a 14-day screening program versus no screening. Patients found to have indicidental AF were commenced on oral anticoagulation to reduce their risk of ischaemic stroke. The researchers followed up the participants for >5 years.

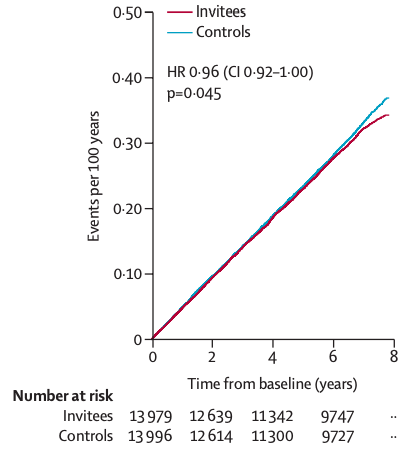

The results can be sliced in different ways but if we look at their main outcome (incidence of ischaemic stroke/haemorrhagic stroke/death/systemic embolism/major bleeding leading to hospitalisation/death), they DID report a lower rate of events (33% of people in the control group versus 32% in the screening group over the whole follow-up period). To translate- the benefit is there, but it’s very small. The relative risk of an event was 0.96 i.e. a 4% reduction in risk. There’s been plenty of debate about what the implications of this result should be.

How would this translate to younger patients? What cost can be justified for this reduction? What if >14 days of screening was done per patient?

GPs are encouraged to perform ‘opportunistic’ pulse checks routinely on their adult patients and there’s a lot of innovation about how to potentially use devices in waiting rooms to screen at lower cost. The UK National Screening Committee is due to publish their report after assessing all the data in 2022-2023 and until then each individual should be evaluated on their own risks and symptoms.

Svennberg, E., Friberg, L., Frykman, V., Al-Khalili, F., Engdahl, J., & Rosenqvist, M. (2021). Clinical outcomes in systematic screening for atrial fibrillation (STROKESTOP): a multicentre, parallel group, unmasked, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01637-8