Athletes and AF risk

Exercise and physical activity are well-known for their benefits in reducing metabolic disease risk and improving cardiovascular health. This is also the case when it comes to atrial fibrillation- exercise and it's consequences (lower BMI, better BP control) are associated with lower incidence of AF and as we discussed last month- may even reduce AF burden in patients who already have the condition.

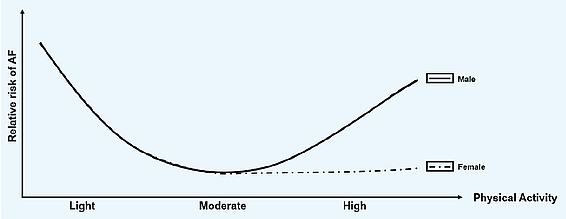

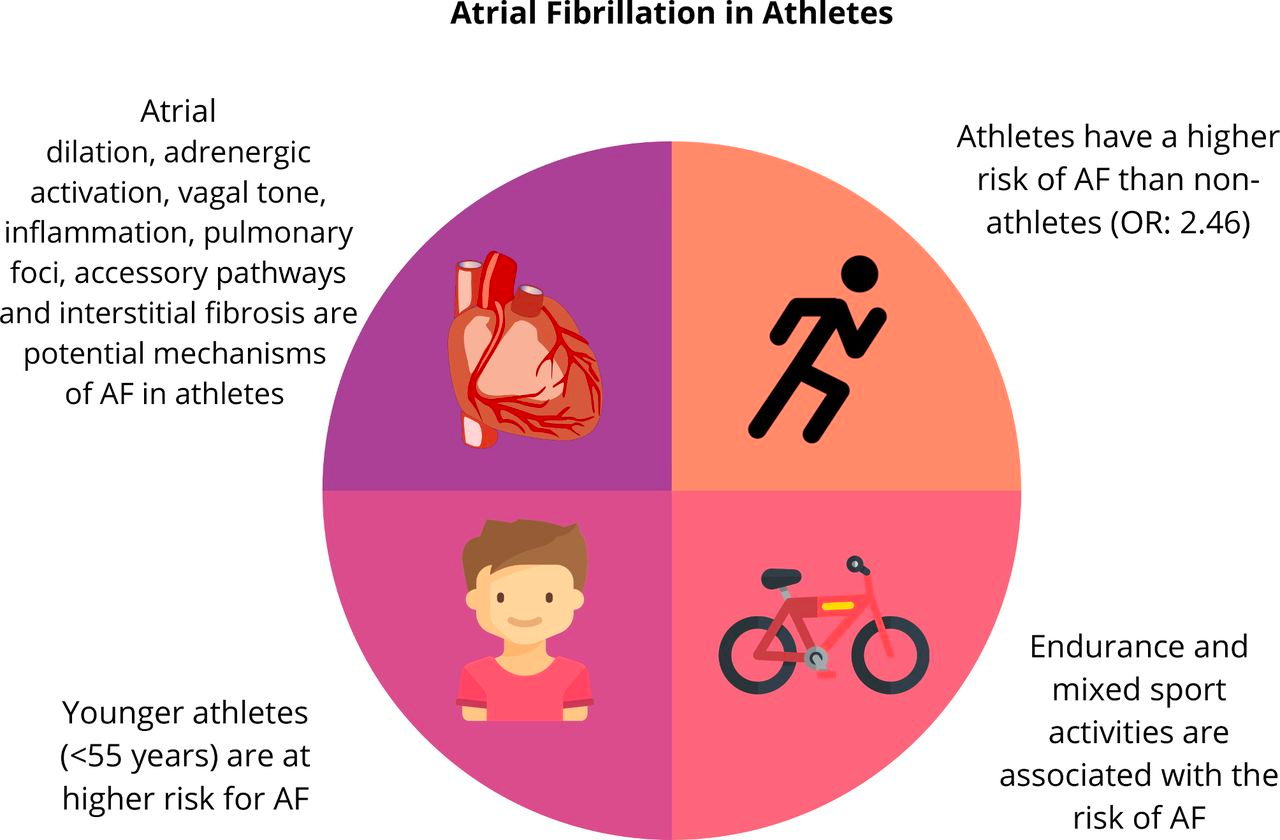

However, when you plot a graph of AF prevalence versus exercise- the relationship isn't a straight line. We see a U-shaped curve, suggesting there is a point above which more exercise means more AF. This finding comes from many observational (case-control type) studies comparing the rate of AF versus non-AF. Athlete is defined by the Sports Cardiology community as ‘an individual of young or adult age, either amateur or professional, who is engaged in regular exercise training and participates in official sports competition’. And the risk of AF in athletes appears to be almost 2.5x higher thank in non-athletes; 3.5x higher risk if we look at people under 55.

Is there such a thing as too much exercise?

First, we should note, that most of the research has studied male athletes, so whether we can directly translate this relationship to women is unclear. In fact, a meta-analysis combining the smaller studies of women together has suggested this relationship may not be seen in women, so more gender-stratified study would be valuable.

So what level of exercise is associated with the lowest AF risk?

Different cutoffs for the ascending flank of the U-curve have been proposed. Some studies use a total accumulated exercise volume (above 1500 hours) whereas others measure the number of hours per week for a sustained period (>5 hours per week). Beyond this point the AF risk has been suggested to rise, but this needs to be balanced against the non-AF health benefits of fitness, reduction in cardiovascular risk factors and the joy that an athlete may experience.

Research suggests that specific types of athletes are at a higher risk of developing AF, with endurance sports being one of the main culprits.

Several landmark studies were conducted in Sweden on participants of the Vasaloppet cross-country skiing event- comparing skiers to non-skiers. Of the 200,000 participants enrolled, and after adjusting for diseases related to AF, it was found that those who completed more races and had better performances had a higher incidence of AF compared to non-skiers. Another study on former professional cyclists showed an AF prevalence of 10% in this cohort, which was significantly higher than a control population (of age-matched golfers).

But why do these findings matter to non-athletes?

The mechanisms by which exercise training increases the risk of AF are complex and speculative. Suggested mechanisms include the raised adrenaline levels during exercise, the changes in heart chamber from higher pressure during exercise and recurrent inflammation with exercise that leads to fibrosis.

Studies of athlete's hearts have led to several fascinating insights into the human physiology. The changes that we see in athlete's hearts share some features with that of elderly patients (higher fibrosis levels, larger chamber sizes, slower resting heart rates)

For the vast majority of the population i.e. the non-professional endurance athletes, this should not impact our lifestyle or behaviour.

The British Association of Sports and Exercise Sciences and the US Department of Health and Human Services recommendation for 150min of moderate-intensity exercise per week seems like a good target. It appears safe to exceed this up to double without negative consequences from an AF perspective. The amount of exercise needed to increase your AF risk is, by definition, extreme. Moderate amounts of exercise appear to be protective against AF and the reduction in heart disease, diabetes, mental health disorders and cancer seen by going from inactivity to exercise is undisputed.

Merghani A, Malhotra A, Sharma S. The U-shaped relationship between exercise and cardiac morbidity. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016 Apr;26(3):232-40. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.06.005. Epub 2015 Jun 18. PMID: 26187713.

Newman W, Parry-Williams G, Wiles J, Edwards J, Hulbert S, Kipourou K, Papadakis M, Sharma R, O'Driscoll J. Risk of atrial fibrillation in athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Nov;55(21):1233-1238. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-103994. Epub 2021 Jul 12. PMID: 34253538.