Depression and AFib

As I continue to analyse the symptom scores and reports from the patients in our AFib research studies, I am struck by how much variability there is in the individual experience. Previous studies by Canadian researchers has shown that the change in the amount of AF after catheter ablation correlates with the severity of AF symptoms. But we don’t know what influences the severity of AF before treatment. We presented some results that the rate of AFib and its irregularity affects whether episodes are symptomatic or not, but this is a general trend we saw across thousands of individuals with AF. There were many exceptions to the rule, and it is unclear to me why.

Emotional state and AF

Whether there is an emotional component that determines the perceived impact and severity of AF symptoms has not been deeply researched. This may be because emotion and mood are hard to measure and something that is beyond the expertise of most cardiologists. It requires collaborative work between psychologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists and, of course, a lot of time and effort from patients to reflect on their mood and mental state. Nevertheless, there is some data that we should consider on the relationship between mood disorders and AF. The remainder of this post will look at one end of the emotion spectrum, and that is the formal diagnosis of depression and its association with AF.

Causation versus Association

Before looking at the evidence, I want to comment on the difference between causation and association briefly.

An association in medicine means the two conditions are seen together, but neither one is the cause of the other, for example, high blood pressure and diabetes. They have shared risk factors like obesity, lifestyle and age, but high blood pressure does not cause diabetes and vice versa. However, Diabetes and Kidney Failure do have a causative relationship. Uncontrolled blood sugars damage the small blood vessels in the kidneys, limiting their ability to filter the blood. The reverse is not true, though; kidney failure does not cause diabetes. So, this is a one-way causative relationship.

Going back to AFib and depression, first, we have to establish if there is an association between the two. Then, we can explore whether the association is a result of shared risk factors or if there is a causative relationship to unmask.

There is an association between AFib and depression

There is no easy way to measure this relationship because depression is not a fixed diagnosis and exists on a spectrum. So it is challenging to label a patient as having a diagnosis of ‘depression’.

However, to try and find a signal, we can look at large registries to compare the rates of AFib in patients with depression to groups without the diagnosis.

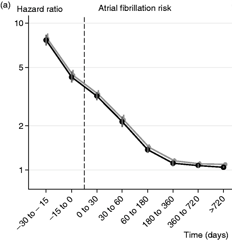

The largest such observational study comes from a National database in Denmark. The investigators analysed the records of 785,254 individuals who were started on anti-depressant medications between 2000 and 2013. They compared the rate of new AF diagnoses in the week prior to initiation (so before the medications were actually started to rule out any confounding effect from the drugs themselves). They found a three-fold higher risk of AF as compared to matched patients who were not taking anti-depressants. Going back to our point about association vs causation- this is very much association- we don’t know if patients were having earlier undiagnosed AF episodes beforehand or whether a trigger event occurred that increases the risk of depression, and AF preceded the co-diagnosis.

The investigators reported some more interesting findings. The AF risk goes down over the 12 months after the antidepressant medications were started. Again, this is an association, not causation. On the one hand, we could say that perhaps treatment of depression reduced the AF risk. Alternatively, the AF risk may just be associated with the initial onset of the depression, so the treatment itself is just a red herring, and it would have settled down anyway.

The investigators also looked back at the risk of AF in the 30 days before the anti-depressant prescription and found an even higher AF risk- more than seven times the risk of AF in matched individuals not taking depression medication. Again, the reason for this is unclear, but the investigators suggest it may be a reflection of the risk of AF associated with untreated depression. And that the depression symptoms may have been more severe in the 30 days prior to the medication prescription, prompting the doctor’s appointment that led to the prescription.

Smaller surveys of individuals with AF have also shown a higher rate of depression symptoms than in people without AF. One small study of 150 patients in Poland reported that 10% of patients with AF had depression symptoms when actively screened for it.

Does depression affect the severity of AF symptoms?

Both anxiety and depression appear to be associated with the severity of AF symptoms, too. A collaborative study between psychologists, academic nurses and cardiologists from North Carolina, USA, evaluated the presence and severity of anxiety and depression with the severity of AF symptoms using validated scoring systems for each. Of the 378 participants who completed the questionnaires, higher depression scores were associated with greater AF symptom severity. Interestingly, there was no association with the amount of AF they were experiencing. Participants who underwent medication or catheter ablation therapy had a significant improvement in their AF severity scores, but no change was seen in their depression/anxiety scores.

Is there a causative mechanism?

No study has demonstrated a convincing causative relationship between depression and AF. This would be hard to do for reasons outlined earlier. In research, the clearest way to demonstrate causation is to give someone condition A and measure whether condition B occurs. That would be unethical for both of these conditions, so we must rely on observational data. The data above suggests that people with AF may have a higher risk of depression, and people with depression may have a higher risk of AF.

A plausible explanation for this bidirectional risk may be that both conditions are associated with increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system—the body’s fight-or-flight hormone system. Further research is needed to understand the importance of this, as it may support wider uptake of therapies that address this component. We have spoken previously about the benefits of yoga and meditation on AFib. In the referenced study, there was a significant improvement in mood and component symptoms of depression.

Conclusion

An association between AF and depression is likely to exist. AF can reduce quality of life as well which improves after treatments like catheter ablation. It seems plausible that on an individual level, the severity of symptoms is a combination of features related to physical health- AF rate, baseline health and fitness and features related to emotional and mental health- a diagnosis of depression, anxiety or a vulnerability to either. However, to measure and prove this is incredibly complex.

The large Danish study: Fenger-Grøn M, Vestergaard M, Pedersen HS, Frost L, Parner ET, Ribe AR, Davydow DS. Depression, antidepressants, and the risk of non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A nationwide Danish matched cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019 Jan;26(2):187-195. doi: 10.1177/2047487318811184. Epub 2018 Nov 19. PMID: 30452291.