Rate control- how fast is too fast?

A rate control strategy describes a management plan to slow down the inappropriately fast heart rate caused by AF, often above 100 beats per minute, sometimes much higher. We know this inappropriate fast rate can be deeply uncomfortable for some people and can lead to heart failure and so rate control should be considered in most patients as part of their initial assessment. This is most commonly achieved using beta-blockers (bisoprolol, metoprolol), calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem) or using digoxin.

Note: a proportion of AF patients have naturally rate-controlled or slow AF but this is not typical and may lead to alternate investigations for the cause of this state.

Many doctors instinctively associate fast heart rates with sickness and seek to slow it down till it comes under control with ‘fast AF’ patients often automatically managed as a priority in the emergency department or even admitted to the hospital until the rate is brought under control. But is this right? And what is ‘under control’? What heart rate should we be aiming for?

Fast AF causing heart failure, chest pains, blackouts or concerning low blood pressures should be managed as an emergency as these symptoms can suggest the heart is not coping with the rate- and so in these cases this is right. Things become greyer when symptoms are minimal or absent and in this circumstance, we are lucky to have some useful evidence to guide best management.

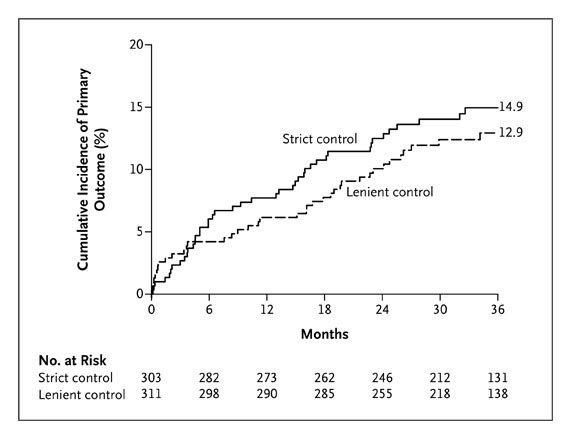

The RACE-II study compared the relative merits of a ‘lenient’ rate control (resting heart rate less than 110 beats per minute) regimen to a strict regimen (less than 80 beats per minute). Prior to 2010, when this study was published, strict control was recommended as it the consensus opinion was that slower = less cardiac problems, hospitalisations and deaths.

So RACE-II enrolled 614 patients across 33 centres in the Netherlands. Through two-weekly consultations increased the rate control medicines till the target heart rate was reached and then followed them up for up to 3 years. Their results were at odds with the consensus opinion- there was no significant difference in the rate of events between the two groups, suggesting no clear advantage in strict rate control. The rate of heart failure was similar, the improvement in heart function seen on heart scans before and after was also similar. Rate control to under 110beats per minute appeared sufficient to reduce the rate of events to that seen in the under 80 beats per minute group. Patients being strictly rate controlled had to make more visits to the hospital, took more drugs and 8% had drug-related side effects i.e. downside without the upside.

So RACE II suggests 110 beats per minute might be the right limit for ‘under control’. However, it’s very important to note that they enrolled patients with permanent AF- i.e. those patients who were not pursuing further rhythm control. And so just because you get ‘rate control’ does not mean symptoms gone. Many patients can still have terrible symptoms despite rate control. In these patients perhaps, RACE II suggests a limit beyond which there isn’t much benefit to be gained from further rate control and other strategies (like rhythm control) should be considered if heart failure or symptoms still persist.

But the two are not mutually exclusive and rate control can often be instated alongside rhythm control strategies too. As we’ve said, the dosage of rate control medicines should be guided by a patient’s symptoms in the first instance and then by their resting heart rate. At-home heart rate monitoring devices, such as the Apple Watch used in the AFFU-AW study make this a much more dynamic process, giving more power to the patient to personalise their own care. However any changes to tablets or doses should be done with the approval of a patients healthcare team, with best care delivered when physician and patient work together rather than any one party in isolation.

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, Hillege HL, Bergsma-Kadijk JA, Cornel JH, Kamp O, Tukkie R, Bosker HA, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van den Berg MP; RACE II Investigators. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1363-73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001337. Epub 2010 Mar 15. PMID: 20231232.