AFib Ablation from outside the heart

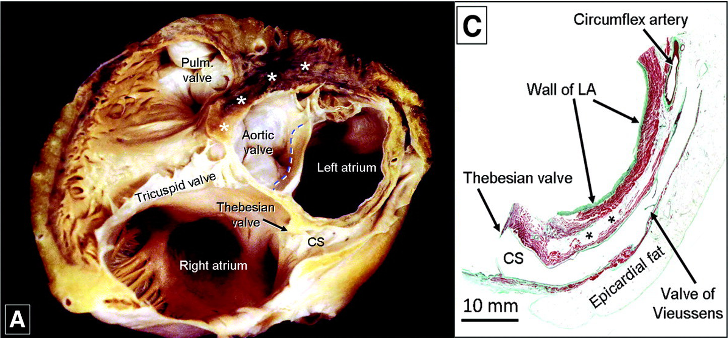

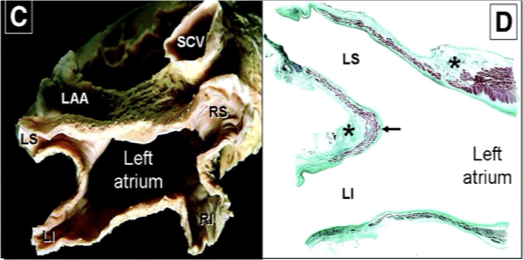

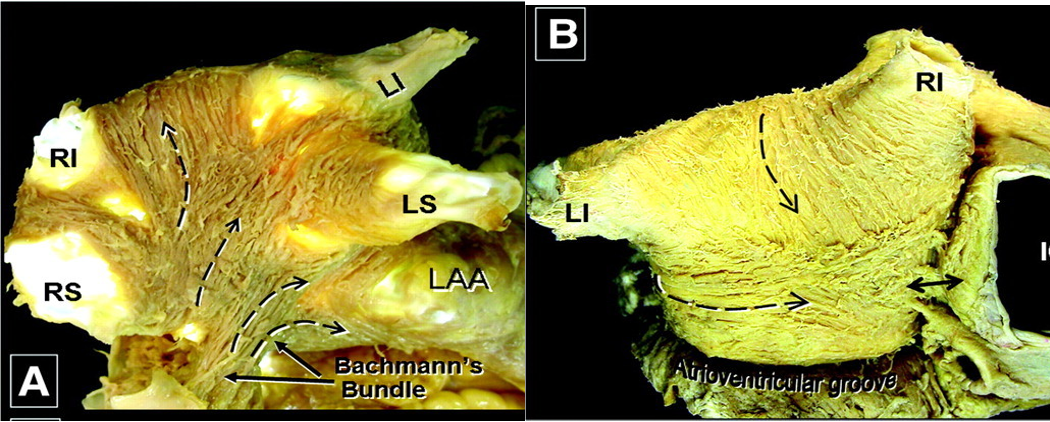

The heart is a three-dimensional structure. The left atrium (the top left chamber of the heart that is targeted during catheter ablation) is only a few millimetres thick. However, in some areas, it can be thicker- up to a centimetre thick. Catheter ablation involves applying energy through heating or cooling from the inside of the heart to ‘turn off’ the electrical activity in specific, targeted areas of the heart thought to be important in AF. When applied from the inside, this energy is sufficient to reach the full thickness of the heart wall in thin regions. However, in thicker areas, it may not be able to fully block the outer layers of the atrial wall. These outer layers are important in some cases of electrical activity. This inability to achieve full-thickness ablation treatment has been proposed as one reason why AF can come back.

Now, importantly, this does not apply to most patients with AF. As we said, most areas of the atrium are thin and ablation from the inside is sufficient. For patients with paroxysmal AF (intermittent episodes that come and go), the arrhythmia commonly originates from the pulmonary veins and this can be targeted very well using the standard internal-only catheter ablation approach.

However, the long-term success rate of this traditional strategy in patients with longstanding AF or AF in the context of structural heart disease is less than 50%. These patients may have more extensive changes to the heart chambers and these may be the patients who could benefit from techniques that more reliably enable full-thickness ablation that can reach the outer layers of the atrium. Ablation can be performed on the outer surface of the heart- so that the energy is applied from the outside inwards and so when combined with traditional ablation from the inside, you have a ‘two-pronged’ approach. Two different strategies to apply ablation from the outside have been tested and shown potential in randomised trials and a third trial is underway in the UK too.

Option 1: The surgical approach

Surgical ablation has been practised longer than Catheter ablation. James Cox, an American Cardiothoracic surgeon performed the Cox-Maze procedure in 1987, wherein he made cuts with his scalpel into the heart wall and then stitched it back together to produce physical lines of electrical block to stop the AF from conducting across the atrium. A modified version is still offered for patients who require open-heart surgery for different reasons (for example if they need coronary bypass surgery or a valve replacement).

For patients with long-standing AF ablation, a much more minimally invasive surgical approach can be taken to deliver heat energy (instead of cuts!) from the outside to areas of the heart that are difficult to reach with catheter ablation is combined with catheter ablation in a technique called the ‘Convergent ablation’ procedure.

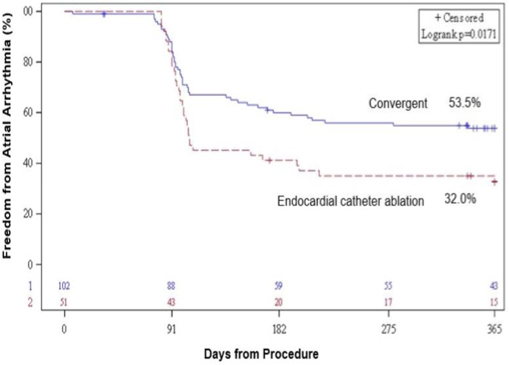

An ambitious trial across 27 centres in the USA and UK randomised patients with long-standing, persistent AF to either undergo ‘Convergent ablation’ (surgical + catheter ablation) vs ‘Catheter ablation’. They enrolled 149 patients with, on average, more than 4-years of continuous AF. Patients that underwent the Convergent ablation had a lower rate of AF recurrence at 12-months (23/99 or 23%) compared to patients in the Catheter ablation group (20/50 or 40%). The difference was even greater if you included patients who came off their anti-arrhythmic drugs only and of the patients that had recurrence, the ‘Convergent ablation’ group also had a lower amount of AF on Holter monitoring at follow-up. However, the surgical approach did introduce risks, although the actual rate of complications was low- 8/102 (7.8%) but included one stroke and bleeding around the heart.

So in these patients with long-standing AF, the convergent procedure may offer greater efficacy but the surgical approach and the associated risks may not be appropriate for everyone.

Option 2: Vein of Marshall Catheter Ablation

The outside surface of the atrium can also be reached without the need for open heart surgery. A network of veins lie on the outer surface of the heart. These originate from an entrance point on the inside of the right atrium. This means a traditional ablation catheter that is passed up the top of the leg and inside the heart for a standard catheter ablation procedure can be passed into this network of veins from the inside of the heart. Not requiring any additional incisions to the body nor prolonged recovery.

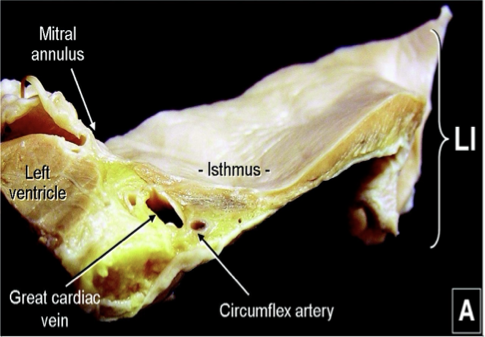

One area that may need treatment if a patient has a recurrence after an AF ablation is the lower left region of the left atrium- called the mitral annulus. This is notoriously difficult to ablate properly, in part because it is thick and can be hard to reach from the insude. Fortunately, it is usually supplied by a small branch vein on the outside surface of the heart called the Vein of Marshall. By injecting ethanol into this very small branch, the supplied area of the heart is essentially ’turned off’ in the way an ablation treatment would effect it.

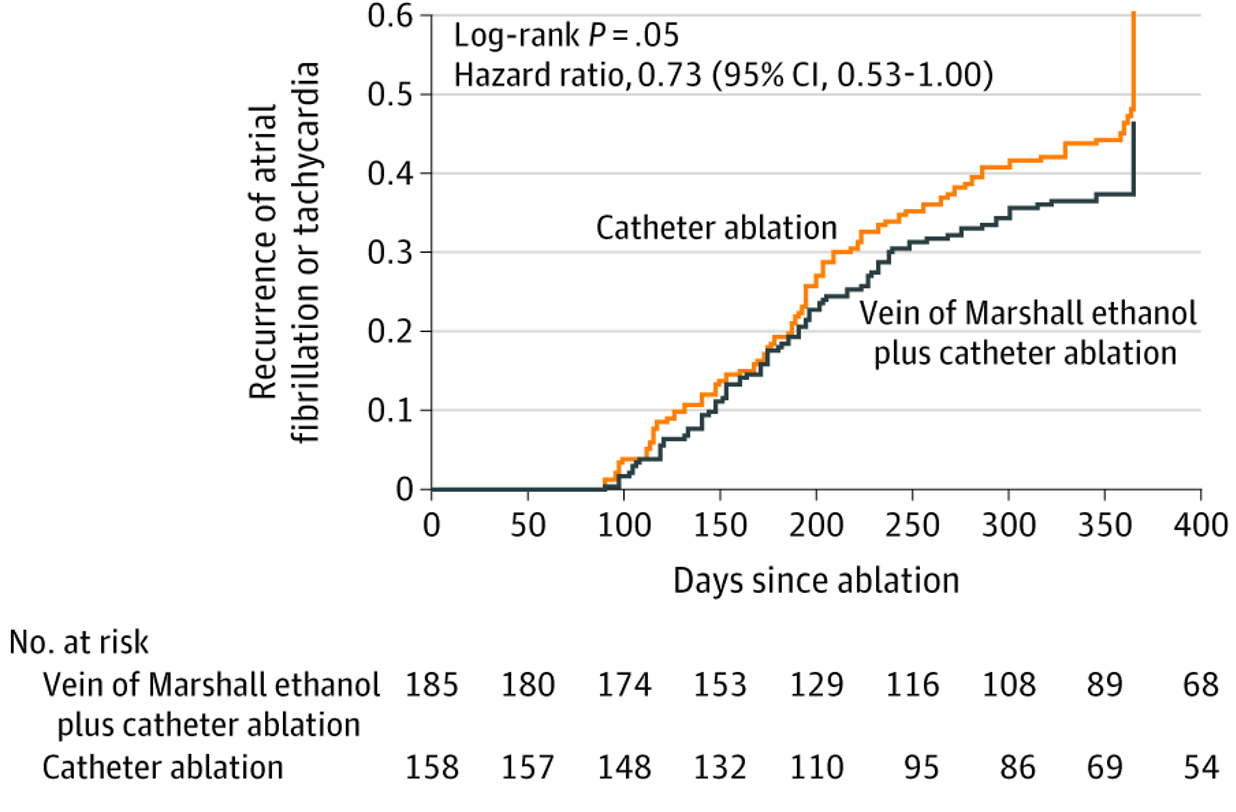

This innovative treatment was trialled in the VENUS trial as an ajdunct to traditional catheter ablation. Again, patients with persistent AF were enrolled and randomised to catheter ablation only or catheter ablation + Vein of Marshall ethanol infusion. These were first-time procedures and the 343 patients enrolled and randomised were followed up for 12 months. The patients randomised to the Vein of Marshall group had a lower rate of recurrence at 12 months (91/185 (or 50.8%) vs 98/102 (or 62.0%)) However, in 30/185 patients randomised to the Vein of Marshall group the target branch could not be accessed and so could not receive the additional treatment, meaning it may not be an option for everybody. There was no significant difference in risks between the two treatment groups.

The next trial: Epicardial ablation

Vein of Marshall ethanol infusion is limited by it only targeting one specific additional region of the atrium. AF progression is unique for each patient and although the mitral annulus (the area that is supplied by the Vein of Marshall) is a critical area needing treatment in many patients with advanced AF, it is not the case for all patients and so this treatment would not be appropriate for many.

The preferred technique to access the heart from the outside would be a non-surgical approach that can reach a broader area of the atrium. The EPIC-AF trial has been approved in the UK. It uses another innovative, non-surgical approach to directly enter the space around the heart by passing the ablation catheter through the skin from under the ribcage. The patient would still need to be put to sleep for the duration of the procedure but the access site is less than a centimetre and patients can walk around or even go home later that same day. Whether the benefits of Convergent ablation can be demonstrated by this non-surgical approach will be evaluated in this study as well as the rate of complications.

Final Thought

A final consideration- what if the ablation energy itself was ‘stronger’? So that the treatment delivered from the inside of the heart would penetrate the full thickness of the heart muscle, thus removing the need for ablation from the outside surface of the heart? This is an attractive proposition. It could improve the treatment quality for all patients with no additional access or techniques required. A new type of ablation energy- electroporation delivered through pulsed field ablation has shown some promise in delivering this. However, in the same ways that the other techniques have been studied, pulsed field ablation will need to be studied and results analysed in the same way before any such conclusions can be drawn.

References:

The intricate images of the histological samples were taken from: Ho SY, Cabrera JA, Sanchez-Quintana D. Left atrial anatomy revisited. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Feb;5(1):220-8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962720. PMID: 22334429.

The CONVERGENT trial: DeLurgio DB, Crossen KJ, Gill J, Blauth C, Oza SR, Magnano AR, Mostovych MA, Halkos ME, Tschopp DR, Kerendi F, Taigen TL, Shults CC, Shah MH, Rajendra AB, Osorio J, Silver JS, Hook BG, Gilligan DM, Calkins H. Hybrid Convergent Procedure for the Treatment of Persistent and Long-Standing Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: Results of CONVERGE Clinical Trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020 Dec;13(12):e009288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.009288. Epub 2020 Nov 13. PMID: 33185144.

The VENUS Trial: Valderrábano M, Peterson LE, Swarup V, Schurmann PA, Makkar A, Doshi RN, DeLurgio D, Athill CA, Ellenbogen KA, Natale A, Koneru J, Dave AS, Giorgberidze I, Afshar H, Guthrie ML, Bunge R, Morillo CA, Kleiman NS. Effect of Catheter Ablation With Vein of Marshall Ethanol Infusion vs Catheter Ablation Alone on Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: The VENUS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020 Oct 27;324(16):1620-1628. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16195. PMID: 33107945; PMCID: PMC7592031.